|

|

|

The Parish poor and the Workhouse

John Rigarlsford

I am indebted to Pat Hase of the WSM Family History Society for her help.

Before the welfare state as we know it. The poor of the parish no matter what the circumstance, had a very harsh existence.

And in some places to this day, being poor or needy sometimes carries the stigma of the situation being the person’s own fault. Previous to the reign of ElizabethⅠthe

poor and needy would have had to beg or rely on the charity of their friends and neighbours for survival.

There could be any number of reasons that could lead to a person or family being reliant on the charity of the parish, and

possibly end up on relief or in the local Workhouse. Often brought about by events over which they had no control, such as being physically or mentally unable to work. Or the

older generations who had become infirm or senile etc and were unable to care

or provide for themselves. There are also many instances of individuals recorded in workhouse and pauper records

as being blind, lunatic or idiot etc.

In a rural area such as ours where agriculture was the main occupation, work would have been very low paid and seasonal. A

bad crop year or an epidemic would be devastating to the livelihood of farmer and worker alike. Many Ag. Lab’s and indeed farmers have been forced onto charity relief or the

workhouse.

Until the coming of the railways in the mid 1800's, Which brought other work possibilities to our region and also a means of

being able to travel and migrate to work in other industries etc. Most males in our area would have been employed on the land.

Most of the girls would have become domestic servants or similar, working in the households of local farms, estates,

landowners and businesses etc.

Many of these young and not so young girls might become unmarried mothers which was a serious offence against the one sided

moral code of the times and was regarded as bringing shame onto the family. (It was not unknown for a member of the local gentry, squire or even a vicar to father children by

their housekeeper)! This would quite often mean the poor girl or woman was banished from her family and sent away to where she was not known and could perhaps pretend to be

a widow. Or she could easily be turned out into the street and possibly end up in the workhouse. There are many instances recorded of single women giving birth in the

workhouse.

Elizabethan Poor Law of 1602

In 1602 an attempt to stop much of the begging and indeed robbery by people on the streets saw the Elizabethan Poor Law

introduced. This at least went some way to providing some means of survival for the poor and needy.

It decreed that each parish would be responsible for the welfare of its own parishioners. To be paid for by voluntary

contributions or from rates raised from landowners and tenants of property worth more than £10.00 per annum.

The 1601 Elizabethan Poor Law divided the poor into two groups

- "Would work but couldn't". The impotent poor - the sick, elderly,

those unable to work - who were to be helped via outdoor relief or in almshouses.

- "Could work but wouldn't". This group were the able-bodied paupers and

it was thought that these people were claiming relief because they were lazy. “They were to be severely beaten until they realised the error of their ways”

- It relied greatly on the parish itself to administrate, and on unpaid, non-professional administrators. Rural

Parishes were small and their finances were feeble so unusually heavy burdens such as a poor crop etc. could be disastrous at parish level.

- Overseers, Justices of the Peace, contractors and Vestrymen who operated the relief could be petty bigots. But the

Poor Law could be more humane, because those responsible for the administration of relief at least knew the recipients personally

Relief was given in variety of ways, such as:

Outdoor relief:

Where the poor who had somewhere to live and could look after themselves, were given relief in kind, such as food or money towards essentials.

Indoor relief:

Where those who were homeless or incapable were given shelter in Alms houses and those forced to go into the village or local workhouse or 'Poor

House'.

Not all parishes had a ‘poor-house’ or village Workhouse. It is not known at this stage if there

was a ‘poor-house’ or workhouse in our parish, or if the homeless and poor parishioners of East Brent were sheltered within an

adjoining parish?

See note on 1841 census below

also

Churchwardens’ Accounts, 1677-1693, 1737-1775.

|

|

The following is extracted

from the Charity Commissioners Reports (1819-1837)

Held at Somerset Records Office.

Parish of East Brent

Mr. Piggott’s Gift.

Upon the table of benefactions in the church of the parish, is the following statement; viz.

Mr. Piggott by his last will and testament, gave 10L to the second poor of this parish,

in the year of our Lord 1655, the interest thereof to be given in money, by the church wardens and overseers, on Easter. day, for ever” ‘This 10L. has never been invested, but

appears to have been received by the Overseers of the poor, and applied to the purposes of the parish, leaving the rates chargeable with the interest: the sum of 1Osh.

is accordingly raised in the regular assessments for the relief of the poor, and given every year by the parish officers in bread to the poor, on or about Easter-day.

GIFTS OF WILLIAM BAWDEN, JOHN CHAPPELL, and JOEL KESZARD.

On the benefaction tables in this church are also the following statements :—

Mr. William Bawden gave 5L to the second poor of this parish, in the year 1708, the

interest thereof to be given in money, by the churchwardens and overseers, on Easter day, forever.

“Mr. John Chappell gave 6L to the second poor of this parish, in the year 1724’, the

interest thereof to be given in money, by- the churchwardens. and overseers, on Christmas-day, for ever.

Mr. Joel Keszard gave 5L to the second poor of this parish, in the year 1742, the interest thereof to be

given in money, by the churchwardens and overseers, on Easter day, for ever.”

The three several gifts Last mentioned appear also to have been received and applied to the uses of’ the

parish. The sum of l6s. as the interest of them, is raised out of the parish assessments, and distributed in bread among the poor, in the same manner as Mr. Piggott’s gift

before mentioned.

JACOB DEAN’s GIFT,

Upon the same Benefaction tables in this church is also the following inscription

Jacob Dean, gentleman, by his last will, gave to the churchwardens and overseers of’ this parish, in,

the year of 1803 the sum of 20L the interest thereof to be distributed on the day after Christmas Day, between 20 poor men who do not receive weekly pay or relief’

therefrom.’’

This sum has also been appropriated to parish purposes, and the interest is raised out of’ the parish rates.

Twenty shillings are annually paid by the parish officers to ‘20 poor men. who do not receive parish

relief.

ROBERT IVYLEAF’S GIFT.

Upon the same benefaction table it is also stated, that “ Mr. Robert Ivyleaf gave

5L. to the second poor of the parish, the interest thereof to he paid out of his estate near Rooksbridge, to be laid out in bread, and given on Christmas day, for ever 1722

The estate at Rooksbridge is a large farm, in the parish of East Brent, the property of the Ivyleaf family,

the tenant (of which pays regularly the sum of 5s to the churchwardens or overseers of this parish, who lay it out in bread, and distribute it among the second poor on

Christmas day.

|

|

Between 1601 and 1834. Application of the old Poor Law was inconsistent, and varied a great deal from area to area.

It soon became obvious that some parishes were more

sympathetic towards their poor, and this tended to result in paupers moving into that area from less generous parishes. To prevent this, parliament passed the 1662 Settlement Act

The 1662 Settlement act.

Was based on the practice of returning paupers to the parish of their residence or birth. Residence of a year and a day was required for a

person to qualify for relief.

|

|

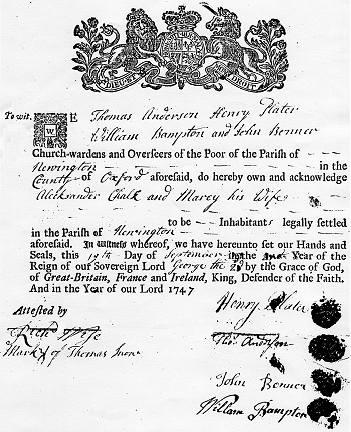

If a labourer moved away from his parish of origin in search of work the JPs issued him with a ‘Certificate of settlement’ saying that if

the man fell on hard times his own parish would receive him back and pay for him to be 'removed'. |

|

A person had to have a 'settlement' e.g. ‘Belong to a

parish’ to obtain relief from that parish. Some of the ways a ‘settlement’ could be secured were:

- Birth in the parish

- Marriage (in the case of a woman)

- Working in the parish for a year and a day

The Settlement Laws sometimes caused problems because they:

- Hindered the free movement of labour

- Prevented men from leaving overpopulated parishes in search of work on the 'off-chance' of finding employment

- Led to short contracts of, for example, 364 days or 51 weeks. A man might lodge in a parish for 25 years, working on

short contracts, and still not be eligible for poor relief later in life.

The Workhouse Test Act

In 1723, the Laws relating to the Settlement, Employment

and Relief of the Poor, allowed the establishment of workhouses where poor relief would be provided.

This could be done either by an individual parish or by

combining of a number of neighbouring parishes, which would share the cost. Between 1723 and 1750, about 600 parish workhouses were established in England and Wales.

The act also introduced the 'workhouse test' - that

anyone who applied for relief would have to enter the workhouse where he or she would be obliged to undertake set work in return for

relief. The principle was that entering the workhouse should be a deterrent to casual in irresponsible claims on the poor rates. Only the truly desperate would apply to 'the

house'.

This principle was continued in the 1834 Poor Law

Amendment Act.

By 1776, there were about 2,000 workhouses, each with

between 20 and 50 inmates. The cost of indoor relief was high; inefficient and harsh workhouse management led to increased social pressure for more sympathetic treatment of the

poor.

However in 1776, Adam Smith published his Wealth of

Nations in which he said that “The State should not interfere and supply relief, but should let the laws of supply and demand operate freely. This would mean that those who could

not work should be allowed to fend for themselves - and starve if necessary - rather than having the State provide any form of relief. Further men would work for any wage rather

than starve themselves and their families; lower wages would benefit employers and reduce the price of food”.

(Not a nice man)!

The Joint parish poorhouse.

Thomas Gilbert, an MP, first attempted to have this Act

passed in 1765. He finally succeeded in 1782.

The Act allowed groups of parishes to form unions and build joint poor-houses for the totally destitute, in order to share the cost of poor relief through 'poor houses' which were

established for looking after only the old, the sick and the infirm. Able-bodied paupers were excluded from these poor-houses: instead, either they were to be provided with

- outdoor relief

- employment near their own homes

Land-owners, farmers and other employers were to receive

allowances from the parish rates so they could bring wages up to subsistence levels. Gilbert's Act is often used to demonstrate the government's humanitarianism but it was even

more important in expanding the scope of poor relief and attempting to bring the gentry into closer involvement in poor relief administration.

By 1796 outdoor relief was given without a workhouse test

because it was a period of widespread distress and unrest. Also many paupers were not able-bodied and parishes were not big enough to cope with the problems.

|

Report from the Commissioners Inquiring into the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws, 1834, p. 303. In parishes overburdened with poor we usually

find the building called a workhouse occupied by 60 or 80 children (under the care, perhaps, of a pauper), about 20 or 30 able-bodied paupers of both sexes, and probably an

equal number of aged and impotent persons, the proper objects of relief.

Amidst these, the mothers of bastard children and prostitutes live without shame and associate freely with the youth, who have also the examples and conversation of the frequent

inmates of the county gaol, the poacher, the vagrant, the decayed beggar, and other characters of the worst description. To these may often be added a solitary blind person, one

or two idiots and not infrequently are heard among the rest, the incessant raving of some neglected lunatic. In such receptacles the sick poor are often immured.

|

Notes on the 1841 census returns for Rooksbridge.

|

In scans of the original 1841 Census enumerators manuscript books for the Parish Of East Brent and Rooksbridge, There appear several

entries for what looks like ["Poor House"] ?

These are indistinct.

The enumerator has written the 'Poor House' entries within the listings for those of Rooksbridge as opposed to East Brent and just before those for "Coothorn" and Edingworth.

I assume that "Coothorn" could refer to what we now know as 'Coothorn Farm' in Rooksbridge Road?

Is it possible that our local 'Poor House' community was situated somewhere between here and the Bristol Road?

The fact that 35

individuals are listed including several families, suggests that more than one property came under this heading?

All appear to be

low paid Farm Labourers etc. and there are a number of elderly individuals included who were possibly unable to earn a decent income?

Note: My thoughts above are only an assumption! And need to be backed up by more research!!

Can anyone offer any further conformation, detail or alternative? JR.

More below...

The 1841 census for East Brent and Rooksbridge

'Poor house'?

Within the enumerators entries for Rooksbridge, there

are a number of individuals and families listed under 'Poor House'

note: Entries within[...]'s are indistinct in Enumerators book.

|

Place |

House |

Surname |

forename |

age M |

age F |

Occupation |

|

'Poor House' |

/ |

Woodward |

William |

75 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

// |

Woodward |

Sophia |

|

60 |

|

|

do |

/ |

Daunton |

John |

75 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

|

Daunton |

Jane |

|

65 |

|

|

|

|

Daunton |

Edward |

3 |

|

|

|

|

// |

Phillips |

Elizabeth |

|

60 |

|

|

do |

/ |

Stevens |

William |

74 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

do |

/ |

Fisher |

William |

70 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

|

Fisher |

Ann |

|

70 |

|

|

|

// |

Fisher |

Jane |

|

[4]? |

|

|

do |

/ |

Edwards |

Robert |

35 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

|

Edwards |

Mary |

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

Edwards |

Pheobe |

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

Edwards |

James |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

Edwards |

Betsey |

|

5 |

|

|

|

// |

Edwards |

Robert |

2 |

|

|

|

Poor House |

/ |

Stevens |

George |

35 |

|

Ag. Lab |

|

|

|

Stevens |

Ann |

|

35 |

|

|

|

|

Stevens |

Emma |

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

Stevens |

Alfred |

4 |

|

|

|

|

// |

Stevens |

Sidney |

1 |

|

|

|

do |

/ |

Pool |

John |

55 |

|

[Tinker]? |

|

|

// |

Pool |

Mary |

|

68 |

|

|

do |

/ |

[Slater]? |

John |

50 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

|

[Slater] |

Sarah |

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

[Slater] |

William |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

[Slater] |

Robert |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

[Slater] |

George |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Radford |

James |

44 |

|

Ag. Lab. |

|

|

|

Radford |

Sarah |

|

43 |

|

|

|

|

Radford |

William |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

Radford |

Elizabeth |

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

Radford |

Edward |

13 |

|

|

|

|

|

Radford |

James |

7 |

|

|

|

|

// |

Radford |

Caroline |

|

12 |

|

|

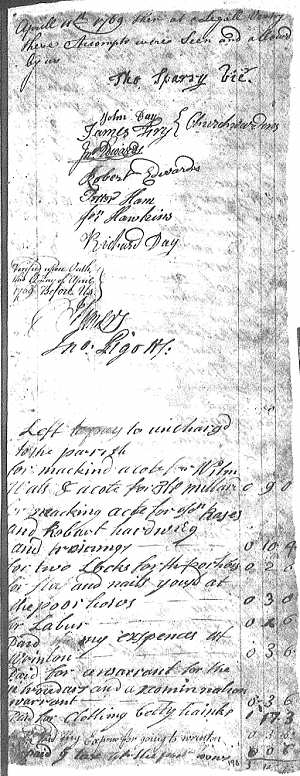

A page from the

East Brent Church vestry accounts.

|

|

From information kindly submitted by Robert Sherwood

(Australia)

The church was responsible for

the distribution of poor relief in the parish and elected overseers

to decide who the needy were.

It does now seem almost certain that prior to

the opening of the Axbridge Union Workhouse, Somewhere in the parish of

East Brent was a 'Poor House' or more likely 'Poor Houses' where the

destitute received aid from the parish.

In the accounts dated 22nd March 1767 is an entry:

"Pd. The Lords rent for the Poor

house 1/-"

There are similar entries at

intervals in the accounts. So it appears that a dwelling or dwellings were

rented by the parish for use of the poor. Also there are expenses claimed

for maintenance of the Poor House. ie:

"For two locks for the poor

house 2/6d"

"For labur 2/6d"

There are records of the monies

spent on individuals.

Also references to expenses for

obtaining warrants of boundary? etc. from Wrington and other places.

Were these in relation to

settlement warrants for individuals claiming parish relief?

|

Go to

the Workhouse!

|

Top

|