"Inside information" on work in:

A

MILK FACTORY.

VERY few Londoners

ever bother to think of how their morning pint of milk really gets

to their doorstep. Little do they realise, until they have lived in

the country and seen it in action, the enormous organisation that is

required to take their pint of milk from the cow to their doorstep.

On being evacuated I was billeted with a dairy-man, and I was thus

able to learn quite a lot about the milk industry, and was able to

go over the Cheddar Valley Dairy Company's milk factory at

Rooksbridge.

Cows are milked at dawn, and also again at dusk. The milkers turn out in all weathers, with their dog in their carts,

each carrying two churns, and sit on their peculiar stools milking.

The cows become accustomed to milking and assemble in a corner of

the field. Often nowadays the herds return to the farm-houses, where

they are milked by electricity. The churns, each containing some 12

gallons of milk, are placed on wooden benches at the roadside, ready

to be collected by vans. The next stage, the collection of the

churns, is done by the factory itself. (A "factory" here is not a

manufacturing workshop but a collecting centre). Vans are sent out

to collect the churns from the neighbouring district. Each full

churn is replaced by an empty, clean one. These vans rush the milk

back to the factory - rush is the correct word, for one never sees a

milk van going slow.

In the

evening the milk is brought into the factory. The vans back against

a raised platform and the full churns are unloaded and inverted over

a large tank, into which the milk drains. This tank supplies the

various plants of the factory. The churns themselves are placed on

one side to be washed. This is accomplished by inverting them over a

jet of steam and swilling them with a hose. The jet, rising from the

floor, makes an almost unbearable noise. The churns are not allowed

to dry before they are rushed out again, once more to be filled with

milk. The whole cleaning process is only a matter of a few minutes.

The milk

itself is fed to the pasteuriser. This machine brings the milk up to

boiling points during its passage through it, thus destroying any

disease. Now the milk is very hot. In this condition it is passed

through the separator, the cream running out at one pipe and

ordinary milk out at the other. skimmed milk results; it comes when

ordinary standard milk is separated to give cream for butter-making.

To cool the milk it is dropped over a series of pipes about 2ins. in

diameter, filled with freezing brine fed from a freezing plant. The

milk is collected in another tank, from which it can be run into

fresh churns or loaded directly into the railway containers to be

sent to London. The churns pass out of the other side of the factory

into vans to be carried to the neighbouring station, in my case

Brent Knoll, from where it is sent to London to be bottled and

delivered. The power for all these various plants comes from a huge

boiler. This furnace is far away from the factory itself, for the

resulting heat would not have a favourable effect on the milk in

summer. The atmosphere in the factory is one of continuous hurry and

bustle. Nobody seems short of some task or other. The noise is

terrific. The machinery rattles continuously; the cooling plant

pumps away methodically; whilst escaping steam from the pasteurising

plant and the jet for cleaning the churns is sufficient to augment

all the other noises into one big din. Another noticeable fact is

the ease with which the churns are moved. The floor is made

throughout of iron grating to facilitate their easy movement. The

workmen, moreover, are extremely clever at rolling them, whether

full or empty. This may look simple to townsfolk, but to roll a full

churn is a very delicate job. The railway provides all transport to

London, the chief consumer for all South England. Thus the milk is

taken to the towns. Never is there a shortage; seldom is any wasted.

The milk once bottled is delivered to the householders in the

morning, the whole process taking place in less than 24 hours.

P. MANNERS (L.6 Modern)

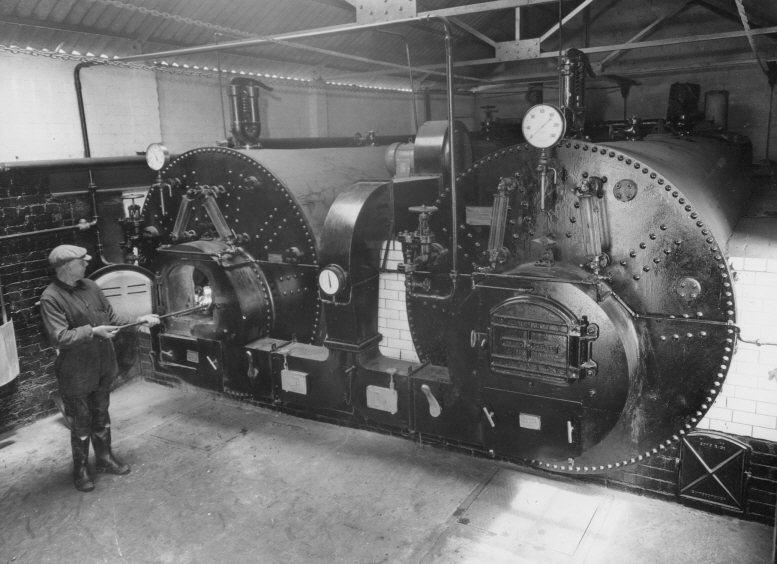

A

typical day at the dairy would

start very early in the morning, say at 4.30am, when the boilerman

would get up steam ready for the cheesemaker.

|

The Early Shift!

Ernie Popham stoking

the coal fired boilers.

During the 1950's

these boilers were converted to heavy fuel oil burners and

were virtually able to maintain the correct head of steam

unsupervised.

It saved a lot of raking and shovelling coals !

Part of the early

morning boilermans duty, was to get a good head of steam to

heat the milk in the cheeseroom ready for the Cheesemaker to

add the starter when he came in.

photo: courtesy R

Brown. |

|

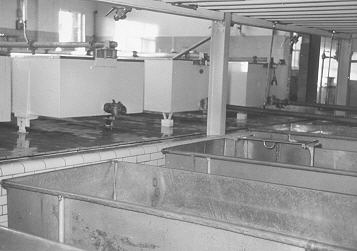

The Cheese maker would arrive at about

5-30am to add a rennet starter to the heated milk which would begin

the 'Cheddar-ing' process.

The seven 1000 gall

milk vats on the upper deck -some seen here- held milk that was

heated and stirred and starter then added at the

correct temperature. (Getting the amount of starter and the

temperature correct is part of the skill of the cheesemaker)!

Once the first part of the process was complete, the curdled

milk was drained into the lower cheddar-ing vats, where the

whey drained from the cheese. The solidified curd is then

cut with large knives, into manageable blocks and

continually turned and stacked until all the whey is

drained. When it is then milled and the salt added.

The milled cheese is then packed into 60lb truckle moulds

lined with cheesecloth. These cheese moulds were then pressed for

several days in huge gang presses to compact and remove any

excess moisture from

the cheeses.

|

Cheeseroom 1980's

Cheeseroom 1947

photo: courtesy R

Brown. |

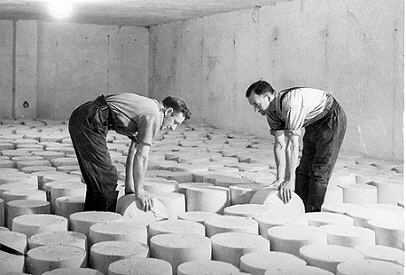

Stan Body and an

assistant turn the maturing cheddars.

photo: courtesy R

Brown. |

When the cheeses were removed

from the presses, they were stamped with vat numbers, dated

and then placed into store.

Here the cheeses were turned

daily while maturing, sometimes up to a year or more, depending on

the flavour required. |

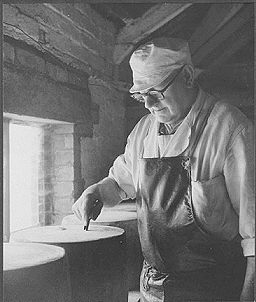

Once

the stored cheeses reached the age of maturity and flavour

required. Using his cheese sampling plug cutter tool. The cheesemaker would sample the batch for flavour

and texture etc.

This enabled him to know how a particular batch would grade

when tested by the wholesalers cheese grader. Once

the stored cheeses reached the age of maturity and flavour

required. Using his cheese sampling plug cutter tool. The cheesemaker would sample the batch for flavour

and texture etc.

This enabled him to know how a particular batch would grade

when tested by the wholesalers cheese grader.photos: courtesy Richard

Brown and Richard Popplestone. |

Frank Page grading a

batch of cheddars |

A standard truckle of Cheddar cheese

weighed 60 lbs. 9 lbs and 4 lbs truckles were also made, along

with miniature 1/2 lbs and 1 lbs waxed cheeses mainly for the

Cheddar tourist trade.

photo

courtesy: Western Daily Press. |

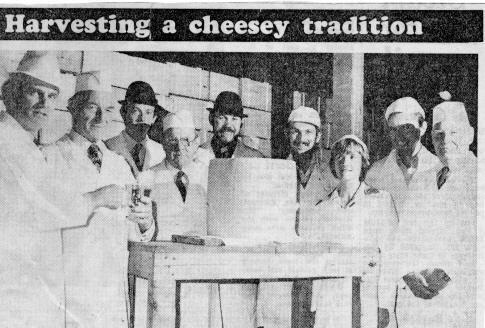

It was always tradition, that a special giant 112 lbs cheese was

made and presented to the East Brent Harvest Home every year! (The

last of these was made and paraded in 1981).

Head cheesemaker Jim

Andrews came out of retirement in 1981 to dress and prepare

the very last Harvest Home cheese, and to receive a tankard

on his retirement, from manager Richard Brown.

Also in the photo are: Steve Perkins. Production Manager,

Stan Burden. Engineer, Dennis Cottle. Area manager, Gilbert

Pike. Cheeseroom foreman, Margaret Poole. Laboratory, John

Holdenby. Bottling supervisor and Pete Lewis. Customer

Liason. |

While the cheese made by CVD was usually made as

60 lbs traditional farmhouse truckles, gradually, with the demand for pre

packed cheese for supermarkets etc, block cheese was increasingly

produced in 40 lbs blocks. Until

the mid 1950's, batches of Caerphilly, Cheshire and Double

Gloucester were also produced.

At its peak, the dairy was

manufacturing over 18,000 tons of cheese per year.

To expand production further would have

cost over £500,000 for a complete refit of equipment and buildings.

The decision was made to expand cheesemaking facilities at the

Horlicks Dairy in Ilminster. And in 1981 after a hundred years, cheese

making at Rooksbridge ended!

|

1964 and two

proud cheesemakers claim another clutch of awards!

Cheesemakers Stan Body

and Jim Andrews show off their Mid Somerset show trophies

photo: courtesy R

Brown. |

|