EAST BRENT CHURCHWARDENS’ ACCOUNTS

1677 to 1693 and 1737 to 1775.

by Robert Sherwood.

This feature shows the important role of the church in governing the parish and its people before the days of the Welfare state'

Published by kind permission of Robert Sherwood (Australia)

(Rob Sherwood is related to the Fry, Norvel and Edwards families of the parish)

Roberts superb website contains in-depth histories of these local family names etc.

at.... http://www.members.optusnet.com.au/rjsherwood/

1677 to 1693 and 1737 to 1775.

by Robert Sherwood.

This feature shows the important role of the church in governing the parish and its people before the days of the Welfare state'

Published by kind permission of Robert Sherwood (Australia)

(Rob Sherwood is related to the Fry, Norvel and Edwards families of the parish)

Roberts superb website contains in-depth histories of these local family names etc.

at.... http://www.members.optusnet.com.au/rjsherwood/

Go to...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recorded in the Churchwardens’ Accounts[i] for East Brent, are the rates collected from the land owners in the parish. Money raised from these rates was used to maintain the church, care for the poor and fund a hospital for injured soldiers. The churchwardens’ accounts along with the church registers, vestry minutes and highway accounts were once kept under lock and key in the parish chest. They are now stored at the county records office.

The rate in the Churchwardens’ accounts was set by the vestry. The vestry was the governing body of the parish and got its name from the small room in the church where the minister put on his garments and robe before conducting a service. Members of the vestry were the vicar, the two churchwardens, the two overseers of the poor and a several other members of the parish. The Vestry nominated the Constable, who acted as the village law officer, the Churchwardens, the Overseers’ of the Poor and the Surveyors of the Highways. These nominations were subject to approval by the Justices of the Peace. The vicar may have chaired the meetings. He was the first sign the vestry minutes followed by the two churchwardens. In East Brent the number of vestry members present at each meeting varied from six to ten. For East Brent two churchwardens were elected each year. They were required to keep a written account of the rates they collected and how this money was spent. Money spent by the churchwardens was referred to as ‘Layings Out’ or ‘Disbursements.’ These disbursements along with the rates were entered in the Churchwardens’ Accounts each year.

For East Brent, two lots of Churchwardens’ accounts survive. They cover the years 1677 to 1693 and 1737 to 1775. The earliest accounts (1677 to 1693) cover a 16 year period. Some of the handwriting is very hard to read and I wouldn’t be surprised if I have made some mistakes when transcribing the records. A typical entry in the accounts book for the years 1677 to 1693 begins as follows.

East Brent. For the year 1677. A rate made for the hospital and maimed soldiers at the vestry, of one shilling in the pound by us Edward Williams and Nicholas Isgar, churchwardens. Robert Dod and George Browne, overseers of the poor.

Following on from the entry above, are the names of the land owners in the parish. Against each land owner’s name is the annual value of their property in pounds and shillings. Next to this is the amount of rates or tax they paid. If the vestry set the rate at one shilling in the pound, then a property owner whose land was valued at 10 pounds paid a tax of 10 shillings that year.

The Fry name appears in the Churchwardens’ Accounts for 1677. The given or first name cannot be read because the page has been torn. The person referred to here was more than likely William Fry. William (Will) Fry appears in the rate assessments from 1678 to 1682, again in 1683 and for the last time in 1688. In each instance William Fry’s land was valued at six pounds.

In 1684, a George Fry is listed in the accounts book. His land had an annual value of four pounds, ten shillings and he paid rates of three shillings and nine pence. George Fry also appears in the accounts books in 1688 through to 1690. In 1691 his land is valued at six pounds. In 1687, 1688 and in 1690, George Fry signs as a member of the parish vestry. In 1689 and 1690, he appears in the churchwardens’ accounts as one of the overseers of the poor. The churchwardens’ for those two years were John Parrott and W’m Bagg. The two overseers of the poor were W’m Symes and George Fry.

George Fry may have been related to William Fry. William may have died sometime around 1688. George Fry married Elizabeth (surname not known) about 1690. They had at least five children, four daughters and a son George who died soon after he was born. George’s wife Elizabeth was buried in East Brent September 22, 1705.

The appearance of William and George Fry in the Churchwardens’ accounts in the latter part of the 17th century is interesting. Add to the mix a Robert Fry who also appears in these records at this time (1679) and a John Fry whose wife Mary was buried in East Brent in 1741, and things become even more intriguing.

Just exactly who these men were and their relationship (if any) to James Fry (c.1710-1776) is not known at this stage.

Hopefully evidence will be found to link them all and take us further back in time with our Fry ancestors.

Following the list of names of rate payers in the parish are the disbursements made by the two churchwardens. A typical entry preceding the lists of disbursements for this period reads…

The layings out of Edward Williams for Church and hospital for the year 1677.

In their disbursements the churchwardens recorded payments made to the hospital, to individual parishioners and for work done by tradesmen and others on maintaining the church. I have selected half a dozen or so entries from the first Churchwardens’ book to show how money raised from the rates was spent to cover the cost of repairs to the church and meet other church expenses. In 1677, the churchwarden Nicholas Isgar paid three shillings for bread and wine at Easter. The following year the churchwarden John Chappell paid four shillings and nine pence for bread and coins at Christmas. That same year Chappell recorded in his accounts.

Allowed myself for to (two) days work for mending the rails and bording (boarding) to (two) windows.’ ‘Paid for boards which I used about the tower windows and the lids, 6 shillings.

An entry further down the page reads..

Paid to John Nell? of Bridgwater the sum of five pounds, five shillings for glazing the windows and mending the leads.

This entry may refer to replacing the glass in the two windows which were ‘boarded up’ by Chappell. The repairing of the lead probably meant that they were leadlight windows. The church organ would have been played at each church service and the organist was paid for his efforts as the following entry shows.

Paid the organ man one pound two shillings and six pence for playing the organ.

Chappell ‘Paid to Fry six pence for a book of Canans.’ Canons are sacred writings included in the bible. I assume this book was intended for the church. Perhaps it still exists and can be found somewhere in the church.

In 1679, fifteen sacks of lyme (lime) were bought at one shilling and tuppence a sack, at a cost of seventeen shillings and six pence. John Gast may have been the plasterer. He was paid a pound for ‘plastering and white lyming the church’

That same year…

Received by me Christopher Crosman, Churchwarden for this present year 1679, one silver challis with a cover, one flagon, one napkin and a table cloth, one woollen table cloth, one pulpit cloth with a cushion, one woollen surplis with other goods belonging to the church this 8th day of July 1679.

In 1680 a fence was built around the churchyard. An entry in the accounts book tells us that timber was purchased for one pound and eight pence and was used for ‘rayling of the churchyard.’ Workmen were paid two shillings when they ‘rayled in the churchyard.’ The following year two shillings and six pence was ‘Paid for the Lord’s rent for the church house’ The vicar of St. Mary’s church at this time was John Russell. He was vicar from 1670 to 1681.

In 1682, the churchwarden John Burrow paid eight shillings and sixpence for 3 bell ropes, which were no doubt used to ring the church bells. The church’s two oldest bells date from 1440 and 1450 and are still in use. Burrow paid eight pence for a lock for the church box and then paid six pence ‘for putting on a lock on ye church box.’ He gave the mason five shillings and four pence for tyling and plastering. John Barnes was given 5 shillings ‘for three days work and nails about ye gutter.’

The following year the two churchwardens’s for the parish wrote…

Rec’d by us William Morris and Thomas Martin, churchwardens for the year 1683. One silver chalice at…and flagon, and white table cloth and napkin and communion table cloth and pulpit cloth and cushion, and green cloth …and other things belonging to the church this 15th day of May 1683. Signed by William Morris. The mark x of Thomas Martin.

Also that same year. ‘Paid the Lord’s rent for ye church houses.’ The amount appears to be five shillings. Similar entries appear in subsequent years. Could the church houses have been the parish poor house? A ‘poor house’ is referred to in the second book of churchwardens’ accounts.

In the Churchwardens’ accounts for 1687, four pounds was spent on lime for the (church) steeple and six shillings and eight pence was ‘spent upon ye workmen and others of the parish when the steeple was pointed.’ Two pounds ten shillings and six pence was paid ‘to Walter Hancok for ramps and boults (bolts) and other things when the steeple was pointed.’ And John Barnes was paid a shilling for a door for the steeple. In 1689, Andrew Hurd was paid a shilling ‘for playing y’e organ at pyfest?’

In 1679, the churchwarden Christopher Crosman wrote ‘I paid Robert Fry two shillings.’ No reason was given for Fry’s payment. There are numerous entries where men were paid for stones which were used to fill the holes and ruts in the parish roads. In 1681, the churchwarden William Show wrote ‘I owed myself for stones to mend the hi wayes, (highways) five shillings and sixpence.’ William Pope was the vicar of St. Mary throughout this period, from 1681to1687.

From 1677 to 1693, part of the revenue raised from the rates was used to pay for the hospital and to provide money for maimed soldiers. Those maimed soldiers may have been Somerset men injured in the first two civil wars fought in Britain. The wars were fought between King Charles 1 and the Parliamentarians who believed they should be able to govern without interference from the king. In 1634 Charles 1, demanded that Somerset provide £8990 for ship money. Nearby Axbridge (which I would imagine included the surrounding parishes such as East Brent) was asked to contribute £30. The first civil war began in 1642. An all day battle was fought in Somerset, at Lansdown Hill in 1643. The Royalists lost between two and three hundred men with many more wounded. The Parliamentarians lost possibly twenty men with less than sixty wounded. The wars ended with the capture, sentencing and beheading of Charles 1. Following the wars there were requests for assistance by injured soldiers and the widows of those men who had lost their lives in battle.

A regular sum was paid quarterly "to the hospital for poor maimed soldiers", and it seems likely that this was the former Woodspring Priory near Weston-super-Mare. This had become a hospital after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and remained so until well into the 18th century. Many parishes in the locality contributed regularly to its upkeep.

East Brent was one of the parishes which contributed money to the hospital. Following the names of landowners in the parish (in the Churchwardens’ accounts) are the ‘layings out for the church and Ospitall.’ (Hospital) The two churchwarden’s for the year 1677, were Nicholas Isgar and Edward Williams. Payments to the hospital were made on a quarterly basis. They were made at midsummer, ‘Paid the Ospitall at Midsomor…’ The amount paid can’t be read because the page is torn. The amount was most likely eight shillings and ten pence. Another payment was made at Michaelmas. ‘Paid the Ospitall at Michalmas, eight shillings and ten pence’ and at Christmas, ‘Paid the Ospitall at Chrismos, eight shillings and ten pence’.

The first Churchwardens’ book gives us some idea of the people and life in East Brent in the 17th century. In the book are the names of the churchwardens and overseers of the poor, along with each land owner or occupier of land in the parish. It also records payments made to individuals. There are numerous references to payments made to men and at least one boy of the parish for hedgehogs, polecats, foxes and sparrows. According to the dictionary a hedgehog is a small insect-eating animal with a pig-like snout and a back covered in stiff spines. The hedgehog is able to roll itself up into a ball when attacked. A polecat is a small dark brown animal of the weasel family with an unpleasant smell. In America they are referred to as skunks. These animals were considered vermin and a bounty was paid on them. In 1677 Nicholas Harris was paid one shilling and sixpence for nine hedgehogs. Mathew Dod and Rob Huxley were each paid two pennies for two hedgehogs they had caught. The going price for each hedgehog was tuppence. Tom Fuller was paid four shillings for foxes and John Shepheard was allowed a shilling for his foxes. James Harris was paid eight pence for polecats. In 1678 William Isgar was paid sixpence for three dozen sparrows. George Fry appears in the Churchwardens’ accounts in 1681. There are three entries that year where George was paid for hedgehogs.

Paid to George Fry for 2 hedgehogs, 4 pence.

Paid to George Fry for 8 hedgehogs, one shilling and four pence.

Paid to George Fry for 7 hedgehogs, one shilling and tuppence.

In 1683, George was paid tuppence (2 pennies) for a hedgehog and in 1684 he was paid for two polecats and two hedgehogs. The payment can’t read because the page has been torn.

Money raised from taxing the land owners was also used to care for the needy. There are numerous entries where money was given to men and women who held a ‘pass.’ They were usually wayfarers (travellers on foot) who asked for help as they passed through a parish. In order to receive help they had to produce a pass or certificate of need. Entries appear as follows.

Gave to three women with a pass, sixpence. Gave to an ould woman with a pass, sixpence. Paid to one man and woman and four children, one shilling.

In the accounts of churchwarden George Browne in 1679, two shillings was given to eight ‘souldiers’ (soldiers ) with a pass. In the churchwarden Christopher Crosman’s layings out for the same year (1779) six seamen were paid one shilling and sixpence. In 1688 three pennies were given to a poor woman who came from Ireland and a shilling was given to a man and his wife and four children (who) ‘came out of Ireland having a pass.’ A Dutchman and a boy were given sixpence. The following year four seamen who ‘suffered a shipwreck’ were given a shilling. In 1690 fourteen Irish people with a pass were given a shilling and Nicholas Harris was paid 8 pence ‘for throwing ye (rope?) at ye cow by his hous.’(house) The first churchwarden’s book ends in 1693.

The second Churchwardens’ book spans thirty-eight years. It starts in 1737 and ends in 1775. The first two pages show the rates collected from land owners in the parish. Most of the rate payers’ names can’t be read because of damage to the pages. No dates are visible. On page three the list of rate payers continues for the first half of the page. These are followed by the ‘Layings Out’ (payments) made by James Edwards for 1738.

James Edwards was my 5th great grandfather. James’ daughter Ann married James Fry junior in East Brent in1769. James Edwards appears often in the Churchwardens’ Accounts. He was a churchwarden and Overseer of the Poor in East Brent for more than thirty years. His parents were James and Ann Edwards. James was baptised November 23, 1714 and buried March 24, 1780.

In his ‘Layings Out’ James was required to give a detailed account of the payments he made from the money he collected from the rates. His entries on page three begin with…

The layings out of James Edwards for the parish of East Brent for the year 1738 as followeth.

I paid John Voan for making a stem to the little bell clapper. Putting him up and expenses, 12 shillings and 4 pence.

The bell clapper is the tongue or striker of the bell. ‘Putting up Mr. Voan’ more than likely meant finding him a room to stay for the night.

Spent when bargained with the glazier, 2 shillings and 9 pence.

Paid for glazing the church window and expenses, 9 shillings.

Paid the vicar’s dinner, 2 shillings and 6 pence.’

The vicar of St. Mary’s at this time was John Wickstead.

I paid for horse hair when I fetched the things from

Bridgwater, one shilling.

I spent at that time 3 pounds and one shilling.’

Bridgwater is a major town fifteen kilometres from East Brent.

Paid John Isgar for blowing the bellows (for the church organ)

2 shillings and 6 pence.

Gave John Isgar for cleaning the church. 2 shillings.

On page 6, the names of the two churchwardens for 1738 appear. They were James Norvil and James Edwards. James Norvel was my 6th great grandfather. His granddaughter Ann Norvel married James Fry senior’s grandson John Fry in 1804. The following are some of James Norvil’s ‘Layings Out’ for the church in 1738.

Paid for bread and wine at Easter, 7 shillings and 8 pence.

Paid for bread and wine at Christmas, 7 shillings and 8 pence.

Paid John Isgar for mats for the church, 2 shillings and 6 pence.

Paid for two bell ropes, 8 shillings

Paid for the caryon cloth. 19 shillings

Paid for the burial cloth, one pound one shilling.

Spent when I bought the caryon cloth and burial cloth, 9 shillings and 8 pence.

Spent when I fetched the caryon cloth and burial cloth, one shilling.

Paid James Yortham for playing the organ, 6 shillings.

Paid for making my rates and on grossing (working out) my accounts,

3 shillings and 6 pence.

On the same page below James Norvil’s account is the following.

May 12, 1739.

Received the full content of this account. I say recorded by me.

John Chappell.

The earliest mention of James Fry senior in East Brent is found in the Churchwardens’ Accounts for 1741. He is listed as one of the land owners in the parish. His land had an annual value of six pounds and he paid rates of three shillings that year. In 1748 the Churchwarden Tho’s Hicks wrote…

Paid for liquor that Fry had in his work. 2 shillings and 4 pence halfpenny.

It is the second last entry on the page and more than likely refers to James Fry senior.

James Fry was my 5th great grandfather. In 1752, he appears in the churchwardens’ accounts as one of the Overseers of the Poor for East Brent. James Fry appears with two other members of the family, James Norvel and James Edwards.

The entry appearing in the churchwardens’ accounts reads…

A rate made for repairing the church and other uses by James Norvel, James Edwards, Churchwardens and James Fry and Richard Day, Overseers of the Poor for 1752.

In his role as one of the Overseers of the Poor, James Fry had to keep a record of his disbursements. That is, any money, clothing or help given to the poor of the parish. These payments would have been recorded in The Overseers’ of the Poor Accounts Books. These books do not appear to have survived for East Brent. That they did at one stage exist is confirmed by the following entry in the Churchwardens’ book for 1750.

Then received of Thomas Colstan and George Gamlon Overseers for ye year 1750, ye sum of 9 pounds and six shillings being money due from them to ye parish as will appear by ye poor book in order to balance ye above account. I say received by me John Ille. (Churchwarden)

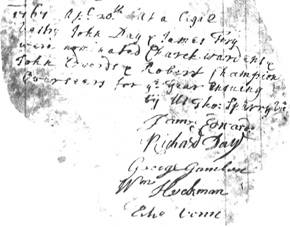

Apart from holding the office of Overseer of the Poor, James Fry was also a Churchwarden. The earliest record of James holding the position of churchwarden is for the year 1765. The names of prospective churchwardens were put forward at a Vestry meeting and after gaining approval from the Justices of the Peace they were elected to office. Opposite is James Fry’s nomination for the job of Churchwarden for the year 1767.

Apart from holding the office of Overseer of the Poor, James Fry was also a Churchwarden. The earliest record of James holding the position of churchwarden is for the year 1765. The names of prospective churchwardens were put forward at a Vestry meeting and after gaining approval from the Justices of the Peace they were elected to office. Opposite is James Fry’s nomination for the job of Churchwarden for the year 1767.

In his role as churchwarden James was required to keep a written account of the rates he collected and how this money was spent (disbursements). The entries were made in the Churchwardens’ Accounts Book.

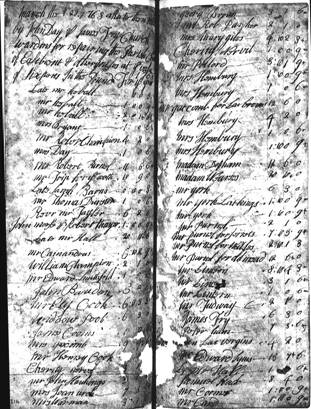

See below for the rate assessment made by John Day and James Fry. The rates that year were six pence in the pound. The far left column of the transcription shows a list of land owners in the parish. The next two columns is the rateable value of their properties in pounds and shillings. The last two columns show the amount of rates to be paid. For example Mrs. Bryant’s property was valued at one pound and she paid six pence in church rates.

March the 28 1768 a Rate then made By John Day & James Fry Churchwardens for repairing the parish church of East Brent and other uses at ye value of sixpence in the pound for ye year 1768.

March the 28 1768 a Rate then made By John Day & James Fry Churchwardens for repairing the parish church of East Brent and other uses at ye value of sixpence in the pound for ye year 1768.

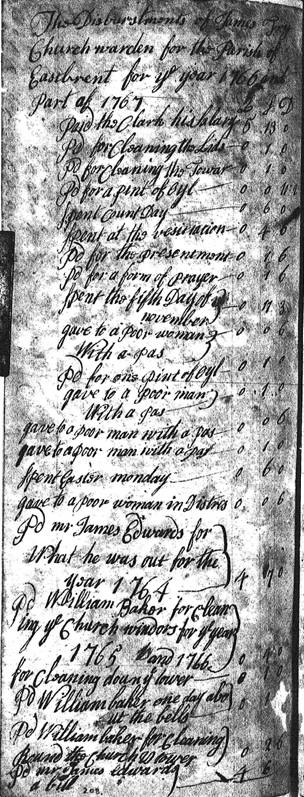

A page headed ‘Disbursements’ followed the list of rate payers in the Accounts book. The disbursements itemised the spending of money collected from the rates. The majority of the rate receipts were used to make repairs to the church and cover other church expenses. On some occasions entries refer to payments made to poor members of the parish who fell on hard times. Below is a copy of the original document with a transcript. It shows James Fry’s disbursements for the years 1766 and 1767.

The Disbursements of James Fry Churchwarden for the Parish of East Brent for ye year 1766 and Part of 1767. ₤-s-d

The Disbursements of James Fry Churchwarden for the Parish of East Brent for ye year 1766 and Part of 1767. ₤-s-d

Paid the Clark his salary. 5-13-0

Pd for cleaning the lids 0-1-0d

for cleaning the towar. 0-1-0

Pd for a pint of oyl. 0-11-?

Spent Count Day 0-6-0

Spent at the vesittatien 0-4-0

pd for the presentment 0-1-6

pd for a form of prayer 0-1-6

Spent the fifth day of November. 0-11-3

gave to a poor woman with a pass 0-0-6

Pd for one pint of oyl. 0-1-0

gave to a poor man with a pass 0-1-0

gave to a poor man with a pass 0-0-6

gave to a poor man with a pass 0-1-0

Spent Easter Monday 0-6-0

gave to a poor woman in distress 0-0-6

pd mr James Edwards for what he was out

for the year 1764 4-7-0

pd William Baker for cleaning ye

Church windows for ye years

1765 and 1766. 0-4-0

for cleaning down ye l…? 0-1-0

pd William baker one day about the bells 0-1-?

P’d William baker for Cleaning round the

Church tower. 0-2-6

P’d mr James Edwards a bill. 4-6-0

The following is an explanation of some of the terms and occupations which appear in James Fry’s disbursements. The first entry refers to him having ‘Paid the clark his salary ₤ 5-13-0.’ (5 pounds, 13 shillings.)

The role of the parish clerk was certainly varied and would have differed from one church to the next depending on the clerk’s age, skills and expertise. One skill he needed to have was the ability to read and write. It was often the clerk’s job to enter baptism, marriage and burial information in the church registers. He may also have been required to dig graves, open and close the church and ring the church bell. In East Brent throughout the 18th century the clerk’s wages were paid out of the rates collected by the Churchwardens. There are entries which refer to the clerk being paid for a day’s work for cleaning the tower. This was the church tower for which he was paid at least a shilling. In another instance he was paid a shilling for cleaning ‘ye lids.’ In most instances the clerk was not named. Entries usually appear as, ‘Paid the Clark his salary.’ In Tho’s Wall’s disbursements for 1746, he names the parish clerk.

‘Paid my part for William Dinwidy for being Clark. 1-0-0.’ (One pound)

Churchwarden Wall paid William Dinwidy one pound for playing the (church) organ. There was also a payment to Dinwiddy ‘for carting ye stones in ye churchway (and) ye street. 5/- (5 shillings)

It is not known how long William Dinwidy was employed as the parish clerk. He continues to appear in parish records for nearly forty years. In 1766 William Dinwidy was one of the collectors of a land tax imposed on property owners in the parish. He collected 6 shillings and 8 pence from James Fry that year. His name appears on vestry meeting minutes, and as a witness to many marriages in the parish. He was one of two witnesses to sign the marriage entry for James Fry’s son James junior when he married Ann Edwards in 1769.

John Edwards disbursements 22 November 1767

The disbursements of Jo’n (John) Edwards for the parish of East Brent for the uses for the poor 22 Nov’br 1767.

One shilling and five pence was paid for a bedcord for Frances Millard.

(A bedcord was a cord or rope interwoven in a bedstead so as to support the bed.)

Paid the Lord’s rent for the poor house, one shilling.

Gave 11 poor people with a pass, one shilling.

Bought Geo Gatt? A pair of stockings (cost) one shilling and 9 pence.

Bought Rich’d Champion a yd? of dowlas at 11 pence per y’d.

Buttons and thread 3 shillings a 9 pence.

Bought 8 y’ds of serge 1.2 per yd. Serge is a strong twilled (woven) worsted fabric used for making clothes)

Three quarters of a y’d of body lining at ?

Half oz (ounce) of thread at 3 pence? Per oz for to make Joan Champion a gown. 10 shillings and 2 pence halfpenny.

Redeem’d (bought back) Frances Millard’s bed 16 shillings. \

P’d for the carriage of Frances Millards bed

An Act was passed in 1723 enabling individual parishes to hire premises to house the poor. The parish of East Brent may have rented such a building to accommodate its poor and elderly, especially those who had no one to care for them. There are entries in the first Churchwardens’ accounts in the later part of the 17th century that refer to the church house and church houses. ‘Paid for the Lord’s rent for the church house.’ These buildings may have housed the homeless members of the parish. In the latter part of the 18th century there are a number of entries that refer to ‘the poorhouse.’ Funds raised from land rates was used to pay a tax or rent for this building. The first reference to the poorhouse appears in John Edward’s ‘Disbursements for the uses of the poor.’ and is dated 22 Mar 1767. It reads…

‘P'd the Lords rent for the Poor House. 1/- (one shilling)

John Edwards may have been the brother of James Edwards.

Part of James Fry’s disbursements in 1769 read…

‘for two locks for the porho’s. 2/- 6d’ (2 shillings and six pence)

‘for flint? and nails yoused at the poor hose’ 3/- (3 shillings)

The next entry follows the two above and may refer to payment for work done at the poorhouse.

‘for labur. 2/-6 (2 shillings and six pence)

The last entry on the page reads…

Paid a tax for the poor hous. 6 (pence)

On the first day of May 1770, the following entry appears in the churchwardens’ accounts book. ‘Paid the tax for the poorhouse. 2/-

For December 11th 1774, according to the monthly pay and disbursements of James Edwards the following appears…

Paid the Common fine for the poor house. 2/-

In the Churchwardens’ Accounts help was given to those in need. This help was given in the form of monthly payments, clothing and medical care

In James Edward’s disbursements for 1774, he lists the following payments (Not all payments have been included here) Seven poor members of the parish received a monthly pay. They were Clement Cook and Mary Watts who both received 8 shillings. Betty Phippon, Jane Vincent and Rob’t Hardige got 6 shillings and Sarah Watts, Ruth Yendols and Jane Gills all received 4 shillings that month. Eight pence was paid for mending Jane Vicent’s shoes and 6 shillings and 10 pence for buying her a coat. Betty Hobs was paid one shilling in time of need and a payment of 4 shillings was made for ‘the tending of Mary Watts.’ Four pounds 6 shillings and 6 pence was paid ‘for a warrant and expenses and keeping John Willcoxs family.’ John Edwards was paid 4 shillings ‘for guard over Jn’o (John) Willcox.’ John Edwards may have been James Edward’s brother. And ‘charged for our/own? horsehire (2 horses, 2 days ?) 10 shillings and 6 pence.’ ‘Paid John Day for horsehire, 4 shillings.’

The following year 1775, James Edwards made the following payments to the poor of the parish. Joan Vincent, Robert Hardridge, Sarah and Mary Watts, Joan Giles, and Betty Yendols continued to receive their monthly pay. Elizabeth Hobbs was given a pair of shoes, Joan Vincent a ‘change’ (underwear?) and a pair of bodices. (This could be bodice the upper part of a woman’s dress down to the waist) Joan Baker was paid 5 shillings for delivering a baby, John Tilby? was given 2 shirts, and wood was given to Mary Watts. When Sarah Watts was buried, a shroud and coffin were paid for by the parish at a cost of 16 shillings and one penny.

Other expenses ab’t Sarah Watts burial? One pound one shilling and a penny.

Land tax assessments

While the Churchwardens’ Accounts gave a good listing of the land owners in the parish as well as the annual rateable value of each land holder’s property, they gave no indication as to where each property was situated. With the Land Tax Assessments[ii] we can get some indication of where their land was located in the parish. According to a land tax assessment made April 22, 1767, James Fry was a farmer and landowner in the tithing of Snighampton, East Brent.

The parish of East Brent was divided into four regions or tithings, one of which was known as Snighampton. Rooksbridge appears to have been included in the Snighampton tithing. A rate of 5 shillings was levied against James Fry’s name that year. There is an entry for the previous year, 1766. The surname Fry appears with the given name erased by a watermark on the page. A tax of 6 shillings and 8 pence was levied on the property. The tax collectors that year were William Dinwidy and Richard Day junior, two local men from the parish. Land tax records only exist from 1766 up until 1832. Records do not survive for the years 1768 through to 1781, a gap of thirteen years.

Robert Sherwood

19 September 2006

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[i] Church of England. Parish Church of East Brent. Churchwardens’ Accounts, 1677-1693, 1737-1775.

Overseers’ Accounts 1761-1776. Vestry minutes 1822-1844. FHL British Film 1595997. Items 12-15.

[ii] England, Somerset, East Brent. Land Tax Assessments 1766-1832. FHL British Film 1526829. Item 9.

| William's letters home |

| Bessies Poems |

| Edwards Letters Home |

| Cheddar Valley Dairy |

| EBPC Archives |

| Methodist |

| Rooksbridge baptist chapel |

| Shops & Tradesmen |

| Rooksbridge Post Office |

| St Marys |

| Village pump |

| War memorial |

| Wellington Arms |

| Workhouse |

| A day at the dairy |

| vicars |

| WardensAcc |

| deanery mag |

| WW1 Exhibit |

| Workhouse Life |

| War Memorial |

| Cheddar valley Dairy |